Group acupuncture following a psychedelic ketamine experience: An integrative medicine pilot study

Dr. Marjorie Navarro

Author's Revised Manuscript

Published in the European Journal of Integrative Medicine, November 5, 2025.

This content is privileged and the author retains all rights under a Creative Commons license.

Abstract

Introduction:

There is a lack of information on bodywork, such as acupuncture, in conjunction with psychedelic medicine. The objective of this pilot study was twofold: to assess the feasibility and tolerability of acupuncture in a group setting as an integrative somatic intervention following a ketamine experience for psychospiritual growth.

Methods:

Participants (n = 15) were enrolled in a group ketamine experience followed by acupuncture one hour after ketamine administration. An optional Participant Feedback Form was administered after the session; responses were reported descriptively as acceptability signals and were not analyzed as formal qualitative data. The Experienced Integration Scale (EIS) was administered within 72 h after the intervention and again after 3 months.

Results:

Of 88 people who requested an eligibility review, 17 were enrolled, filling the study in 20 days. Fifteen attended their scheduled sessions, yielding an 88% retention rate. Initial EIS scores ranged from 45% to 100% (mean 74%), with follow-up scores obtained from 6 participants after 3 months. Feedback from 5 participants described the acupuncture as grounding, calming, and valuable, with one suggesting more time for treatment. Together, these findings suggest that acupuncture after a ketamine experience is feasible and well-tolerated in healthy volunteers seeking psychospiritual growth.

Conclusion:

Participant enrollment and retention rates show substantial patient interest in utilizing acupuncture and sound meditation to support psychedelic therapy. Further research is warranted to explore the potential benefits of acupuncture in conjunction with psychedelic therapy. Such research may inform care for individuals who are currently using these therapies separately, as well as those seeking more integrated approaches.

Registration:

The study is registered at the United States Clinical Trial Registry (NCT06070090).

Funding:

No funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Keywords: Acupuncture, Feasibility Studies, Integrative Medicine, Ketamine, Pilot Projects, Psychedelic Assisted Therapy

1 Introduction

1.1 Ketamine as a psychedelic therapeutic agent

Psychedelics, or psychoplastigens, are a broad class of hallucinogens capable of altering perception, mood, and cognition through their neurological effects [1]. Ketamine is considered a non-classic psychedelic because it acts primarily on glutamate receptors, yet it similarly enhances neuroplasticity and yields lasting therapeutic benefits [2]. Research indicates efficacy across a wide range of mental health conditions [3], with benefits persisting for at least four weeks [4], though longer-term outcomes remain under investigation. Ketamine-Assisted Psychotherapy (KAP) combines sub-anesthetic ketamine dosing with therapeutic support, and evidence suggests outcomes are optimized when patients actively engage in integration, reflection, and deliberate life changes with professional or community support [5–7]. Music is often incorporated into KAP, and a growing body of research links music to enhanced neuroplasticity and social connectedness [8,9]. It has been postulated that ketamine and serotonergic psychedelics open a “critical window of plasticity” in the frontal cortex during which targeted stimulation may augment adaptive neural changes [10]. While the half-life of ketamine is estimated at 1–3 h in humans, a single subanesthetic dose of ketamine can increase dendritic spine density in the medial prefrontal cortex within 2–4 h of administration, with these neuroplastic effects lasting up to 2 weeks [10,11]. This raises the possibility that additional interventions, administered within this window, could support integration and extend therapeutic benefits.

1.2 Acupuncture, sound meditation, and psychedelics

Acupuncture was selected for this study as a candidate concomitant intervention in psychedelic care because of its potential to address biopsychosocial and somatic aspects of integration [12]. Models such as Psychedelic Harm Reduction and Integration (PHRI) emphasize somatic therapies to reduce physiological stress, promote bodily awareness, and ground patients after psychedelic experiences [13]. Acupuncture is known to elicit sensations that “focus attention and accentuate bodily awareness” [14], and has shown benefit in conditions across the depression–anxiety spectrum [15,16], possibly through serotonin modulation [17], vagal stimulation, and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis regulation [18]. Transient anxiety or distress is not uncommon following psychedelic use, and although lasting negative outcomes are rare, distress during periods of heightened plasticity may diminish long-term benefits [19]. Trauma-informed approaches, such as those informed by Stanislav Grof’s Perinatal Matrices and the associated acupuncture treatments [20], highlight further potential.

Group acupuncture models additionally offer unique advantages by reducing cost, fostering social support [21], community empowerment [22], and pro-social behavior through shared parasympathetic activation [23,24]. Psychedelics themselves have historically been administered in group settings [25], where adequate social and psychological support enhances integration [12]. Sound meditation with vibrational instruments such as singing bowls, gongs, and bells also supports relaxation, mood, and spiritual well-being [26,27], and has been incorporated into psychedelic-assisted therapy. Some licensed acupuncturists are exposed to traditional East Asian use of psychoactive medicinals [28,29], positioning them to offer integrative care in this emerging therapeutic landscape.

1.3 Study purpose

Current evidence highlights ketamine’s potential as a psychedelic therapeutic agent [3], the importance of integration practices for sustaining benefits [12], and the role of somatic interventions such as acupuncture in holistic care models. Yet little is known about how acupuncture may function as an adjunct to psychedelic therapy, particularly in group-based designs that emphasize connection and collective integration. To address this gap, we conducted a pilot study of group acupuncture following a group ketamine experience. Because ketamine induces a short-lived “critical window” of heightened plasticity (beginning ∼2–4 h and extending up to two weeks) [10,11], we paired individualized acupuncture ∼1 h post-ketamine; not to test efficacy, but to assess feasibility: interest and tolerability of same-day group acupuncture, session logistics, and practicality of remote outcome capture (EIS at 24–72 h and 3 months). Acupuncture, a somatosensory-guided mind–body therapy, accentuates interoceptive awareness [14], shows benefits across depression–anxiety spectra [15,16], and may modulate serotonergic and vagal/HPA pathways involved in stress regulation [17,18]; in groups it has been associated with increased parasympathetic tone and social coherence [23,24]. We enrolled healthy volunteers seeking ketamine-assisted experiences for personal and psychospiritual growth; in this feasibility cohort a specific psychiatric diagnosis was not required. Findings from this cohort can help guide the design of future controlled clinical trials in patient populations.

2 Methods

The AOMA Institute of Graduate Studies Institutional Review Board approved the study (Project 23C.MN), and written informed consent was obtained from all subjects before participation. The study is registered at http://clinicaltrials.gov (NCT06070090).

2.1 Design

This pilot study takes the first steps in looking at how acupuncture might fit into ongoing research on ketamine-assisted psychotherapy. Here we’re mainly asking how feasible acupuncture is as a somatic intervention in this setting. Based on the ‘rule of 12’ for pilots with continuous variables and a margin of error for participant withdrawal [30], three three-hour sessions with 4–6 participants each were held between October 29, 2023 and December 1, 2023 at Cardea Ketamine Space in New York City.

The acupuncture treatment approach prioritized balancing individual post-ketamine pulse qualities, as described in Appendices A-D, while also supporting any mind-body transformation goals shared by participants. For this reason, adaptive individualized treatments rather than a predetermined point prescription were factored in. This design is in accordance with the approach of the ketamine therapy team, which seeks to support personal or collective transformation through ‘unintegration.’ This concept, developed by Dr. D.W. Winnicott, refers to a state of being nimble and receptive to the experience of where a journey leads [31]. Quantitative information, or patient retention, was recorded. Feedback was solicited by REDCap links, both 24–72 h after the event and as a 3-month follow-up, in order to recollect participant experience and formulate considerations on compliance with digital outcome measures.

2.2 Inclusion, exclusion, and screening workflow

People were eligible for inclusion if they were between the ages of 18 and 65, able to complete the English-language instruments on their own, and provided written informed consent. The overseeing IRB recommended this age range to exclude potentially vulnerable populations; individuals who were pregnant, breastfeeding, or terminally ill were also excluded. Participants were recruited using ClinicalTrials.gov and clinicians’ email newsletters, then enrolled consecutively during a predefined recruitment window.

This feasibility cohort comprised essentially healthy volunteers seeking ketamine for personal and psychospiritual growth; a formal psychiatric diagnosis was not required. All candidates completed (i) a clinical psychotherapy intake and (ii) a medical evaluation by the prescribing physician to confirm suitability and to rule out contraindications to ketamine. Screening occurred via a HIPAA-compliant patient-portal questionnaire with telehealth physician review approximately two weeks prior to the session; pregnancy status was reconfirmed within 24 h of dosing. As an additional day-of safety check, pre-dose blood pressure was required to have an upper limit of 150/90 (see Section 2.3).

Exclusion criteria (IRB-guided/clinical) included: pregnancy or breastfeeding; terminal illness; current or past psychotic disorders (e.g., schizophrenia-spectrum); unstable cardiovascular disease or uncontrolled hypertension; inability to complete study instruments; and medications judged by the prescribing physician to pose risk or be contraindicated with ketamine. Two candidates were ineligible per a priori IRB criteria (terminal illness, n = 1; age >65 years, n = 1). No candidates were excluded by the prescribing physician for ketamine-related medical or psychiatric contraindications. Research on healthy subjects shows that subanesthetic ketamine is characterized by an altered state of consciousness similar to other psychoactive drugs (e.g., psilocybin) [32]. A 2021 systematic review found no reports of ketamine use/misuse following treatment with ketamine, nor evidence of transition from medical to non-medical ketamine use [5]. The full screening instruments are provided in Appendix A.

2.3 The ketamine therapy

After arriving on the day of the session, each participant’s blood pressure was checked to ensure that it was in a safe range with an upper limit of 150/90. Of 88 individuals who requested an eligibility review, two did not meet eligibility due to IRB criteria (terminal illness, n = 1; age >65, n = 1). The remaining non-enrolled individuals declined participation primarily because of scheduling conflicts or out-of-pocket cost; precise counts of these reasons were not tracked in this feasibility pilot. To encourage a creative and playful approach to the experience, participants engaged in a group art activity, during which participants briefly shared with the whole group their goals for the day. Participants then reclined in the group treatment room and self-administered a subanesthetic intranasal initial dose of 90–120 mg of ketamine under direct supervision. The ceremonial space holder began playing music (mostly vibrational instruments) for sound meditation. After 10 min, participants were invited to add to their dose if they were not yet feeling effects, and the therapist assisted anyone who chose to do so. Once the acute effects of the ketamine begin to subside, 60 min after the initial dose administration [33], the live sound was transitioned into recorded ambient music at a lower volume, allowing for communication between the participants and the acupuncturist.

2.4 The acupuncture

The acupuncturist was licensed to practice in New York state and had over 12 years of experience after completing 5 years of full-time academic studies. The acupuncturist approached each participant individually and asked for consent before examining their pulse and tongue. Four participants (numbers 2, 6, 10 and 13) had discussed specific symptoms with the acupuncturist prior to the day of the session, including areas of pain, mental-emotional disposition, and other physiological symptoms. Two participants, numbers 9 and 15, had previously received treatment from the acupuncturist. If no specific treatment goals were shared directly with the therapist or during the ketamine session, treatment points were selected based on the participant’s overall pulse quality, tongue, body palpation, and intake data.

Classical acupuncture treatments, as opposed to Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) point prescriptions, were used. Classical is the general term for the acupuncture approach based on the understanding that the primary pathology is an impairment of natural physiological motion or transformation [34]. Treatments are individualized using environmental information and patient presentation rather than a more allopathic approach of selecting from a point palate based on symptoms. Visual appearance of the tongue, as well as pulse and body palpation, were used to customize each treatment to the individual on the day of the session as described in Appendix D.

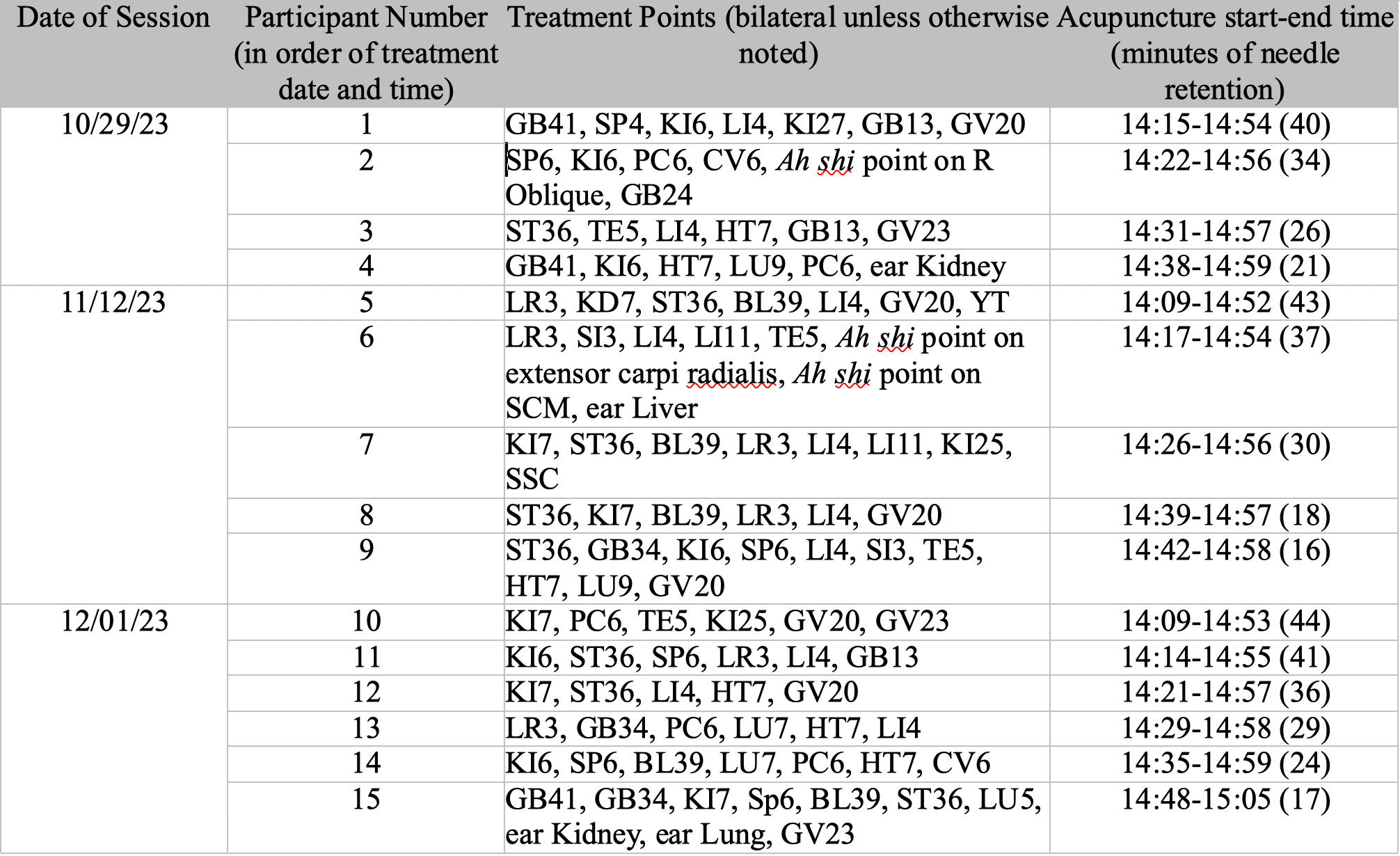

The general locations of the points selected were shared with the participant to gain their consent for treating those areas before needle insertion. All participants were lying supine or reclining on cushions. DBC brand needles, sizes 0.20×30 for body points and 0.16×15 for auricular and scalp points, were utilized. The treatments are summarized in Table 1:

Table 1: Acupuncture Treatment Data

The number of needle insertions per participant ranged from 9 to 19 with a mean of 13. Out of the total of 107 points needled, there were 32 unique locations (counting the four points that make up EX-HN1 as one location) with 21 of them repeating in multiple treatments. Acupuncture points correlated with Grof’s Perinatal Birth Matrices [20] were deemed appropriate to support mind-body transformation goals in 10 of the 15 participants. Treatment point selection was limited to those accessible with the participant in a supine position, and with the participant fully clothed. The depth of needle insertion was ying level, or into the subcutaneous muscle or fascia, with a muscle twitch response sought with manual stimulation on the Ah shi points in proximity to myofascial trigger points. Because needle insertion was more time-consuming than needle removal, participants who were needled towards the start of the session had longer retention than those who were needled later in the session, ranging from 16 to 44 min with a mean of 30.

Acupoint selection was not arbitrary but followed classical acupuncture principles, with points chosen based on pulse quality, tongue inspection, Spirit points relevant for psychospiritual growth, and any symptoms disclosed by participants. Selection was also limited to points accessible in a group setting where participants were clothed and supine. The full rationale for individualized acupoint selection is provided in Appendix D.

To balance real-world Classical practice with reproducibility, we pre-specified operational boundaries and decision rules (full framework in Appendix B). Delivery limits included: single session in a group room with participants clothed and supine or reclining; no electroacupuncture; DBC sterile needles 0.20×30 mm for body points and 0.16×15 mm for auricular/scalp; target needle count 10–16 (observed 9–19); typical retention 20–40 min (observed 16–44). Auricular points were used only in participants with prior tolerance to auricular acupuncture. Point selection followed day-of findings and participant preferences with the following rules: distribute points across extremities and scalp unless the participant requested otherwise; include 1–2 Spirit points and optional selections mapped to

Grof’s Perinatal Matrices when aligned with pre-session themes; for “excess” pulse/tongue presentations prioritize yin meridians and lower-body calming points; for “deficient” prioritize yang meridians and upper-body activating points; if localized pain was reported, include gentle local Ah shi needling. A one-page treatment checklist, fidelity items, and a deviation log are provided in Appendices A-D to support replication and monitoring.

2.5 Feasibility data analysis

The feasibility of the study design was analyzed using the enrollment and retention rates as well completion rate for the outcome measures administered. Participants’ feedback about the acupuncture sessions – specifically, what they liked most and what they would like to change – were transcribed from the REDCap survey, in Appendix E, into the results to help guide future research study design. Data were captured in REDCap and analyzed in Microsoft Excel 365.

- Enrollment rate = (Number enrolled) ÷ (Number screened for eligibility [i.e., individuals who requested eligibility review]).

- Retention rate = (Number who attended a scheduled session) ÷ (Number enrolled).

- Group-session completion rate = (Number who received acupuncture in the group room) ÷ (Number who attended).

- Initial EIS completion rate = (Number who completed the 24–72 h EIS) ÷ (Number who attended).

- 3-month EIS completion rate = (Number who completed the 3-month EIS) ÷ (Number who attended).

- Feedback form completion rate = (Number who submitted the optional feedback form) ÷ (Number who attended).

- ‘Screened for eligibility’ denotes all individuals who requested an eligibility review during the recruitment window; ‘attended’ denotes participants who arrived and participated in the scheduled ketamine session.

2.6 Experienced integration scale

The Experienced Integration Scale (EIS), in Appendix F, was administered to explore whether participants could meaningfully report on their sense of integration after the combined ketamine and acupuncture experience, thereby informing the practicality of using such measures in future studies. This scale was developed by a group of researchers defining integration as, “the process by which a psychedelic experience translates into positive changes in daily life” with the internal qualities of feeling “Settled,” “Harmonized,” and “Improved” identified as the experiential hallmarks [35].

The EIS was administered by REDCap links to all participants the day after the session as well as 3 months from the date of the sessions. The follow-up at 3 months was chosen as a timeframe just beyond previously reported duration of positive response from ketamine therapy [36]. The instructions read: “Please state your level of agreement with the following statements, considering the time period since your most recent psychedelic experience. If you have already filled out this questionnaire, indicate your responses only with respect to the time period since you last filled out the questionnaire. Answer as honestly as possible. There are no right or wrong answers. At any given time your responses will naturally vary between lower and higher scores.” Each item was rated on a 5-point scale (1=Strongly Disagree, 2=Disagree, 3=Neither Agree or Disagree, 4=Agree, 5=Strongly Agree). Patient experience feedback was solicited by way of an optional form also administered by REDCap link the day following the session. Open-ended comments were collected to assess acceptability and are reported descriptively; no qualitative methodology (e.g., purposive sampling, coding/thematic analysis, or saturation) was undertaken, so formal qualitative reporting checklists (e.g., SRQR/COREQ) are not applicable.

EIS scoring and analysis. The EIS comprises 12 items (Likert 1–5). For each participant we computed a raw total (range 12–60) and a percent-of-maximum-possible (POMP) score using: POMP = (Total ÷ 60) × 100.

We also summarized subscale item means for Settled (3 items), Harmonized (5 items), and Improved (4 items). Given the single-arm feasibility design, analyses were descriptive only; we report means, standard deviations, and ranges for total/POMP scores and for subscale item means. No imputation was performed; only available data were analyzed at each time point. Data were captured in REDCap and exported for analysis in Microsoft Excel 365.

2.7 Safety monitoring and adverse events

Safety was monitored throughout the ketamine and acupuncture sessions by the clinical team (psychotherapist and licensed acupuncturist). Pre-dose blood pressure was verified with an upper limit of ≤150/90 prior to dosing; participants were observed continuously in-session; any unsolicited symptoms were documented. After discharge, participants could report undesirable effects via the optional post-session REDCap form or by contacting the team directly. Events were characterized post hoc by severity (mild/moderate/serious) and attribution (related/possibly related/unrelated). No serious adverse events occurred.

3 Results

3.1 Participant characteristics

Participants (n = 15) ranged in age from 28 to 64 years (mean 41). Most resided in New York City (13/15, 86.7 %): Bronx (n = 1), Brooklyn (n = 4; ZIPs 11225×3, 11237×1), Queens (n = 1; 11101), Manhattan (n = 7; 10004, 10012, 10023, 10025, 10026, 10031, 10128); others lived in Long Island (11704) and Tucson, AZ (85705). Participants reported their gender identity as Cis Female (n = 11), Cis Male (n = 3) and Non-binary or Gender Non-confirming (n = 1). Race/ethnicity self-identification of participants was White/European-American (n = 9), multiracial (n = 4: 1 Latinx + another identity; 3 Asian + White/European-American), Black/African-American (n = 1) and another identity (n = 1). Socioeconomic variables (education, occupation, income, and religion) were not collected in this feasibility pilot. A summary appears in Table 2.

Table 2

| Characteristic | n ( %) or summary |

|---|---|

| Age, years | Mean 41; range 28–64 |

| Gender | Cis Female 11 (73.3); Cis Male 3 (20); Non-binary or Gender Non-conforming 1 (6.7) |

|

Residence

|

New York City total 13 (86.7)

|

| Race/Ethnicity | White/European-American 9 (60); Multiracial 4 (26.7)*; Black/African-American 1 (6.7); another identity 1 (6.7) |

Table Footnotes

-

⁎Multiracial detail: 1 Latinx + another identity; 3 Asian + White/European-American.

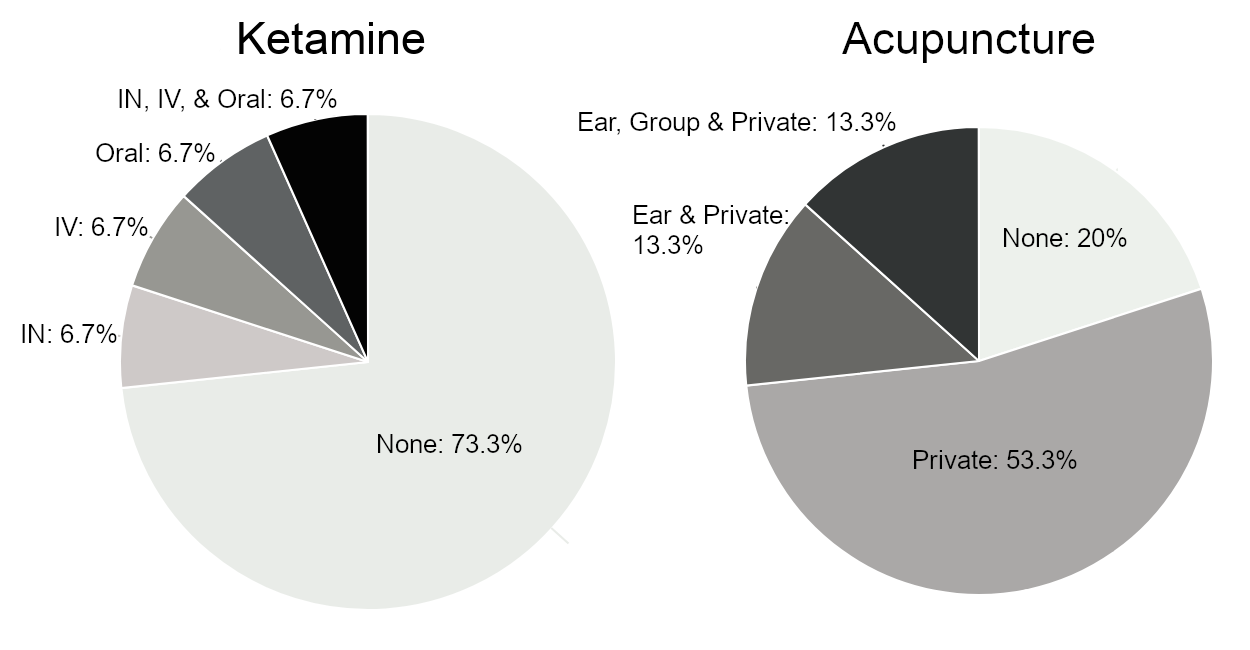

Participants were asked to report previous ketamine and acupuncture experiences, and their responses are shown in Fig. 1. Most participants did not report previous prescription ketamine experience but had experienced some type of acupuncture. Both participants reporting previous intranasal ketamine experience had previously been treated at Cardea. Previous auricular acupuncture experience was explicitly asked about because this practice is commonly used in group settings, and studies indicate acupuncture along the auricular branch of the vagus nerve may be particularly useful in stress or anxiety and depression-reducing treatment [37].

Figure 1: Participants’ reported previous experiences with ketamine and acupuncture.

The prescribing physician medically cleared all participants after a structured history/physical and psychotherapy intake; IRB exclusions (pregnancy, breastfeeding, terminal illness) applied. No unstable medical conditions were identified at screening, and all participants met the day-of-session blood pressure safety criteria prior to dosing. This feasibility cohort comprised healthy volunteers. Physician-collected screening details (e.g., comorbidities, medication/supplement lists, alcohol use) were not retained in the research dataset.

3.2 Participant experiences

The feedback provided by 5 participants through the optional form suggests that the acupuncture following the group ketamine track had a positive impact on their experience and that it was generally pleasant and valuable. One participant described the acupuncture as both a “grounding place post-ketamine experience” and a “calming close.” Another participant described the acupuncture as “relaxing and comforting.” One participant suggested that more time and points for the acupuncture would have been beneficial, while recognizing that the structure of the overall session and the group setting limited the time available. Two participants chose to leave the group treatment room during their ketamine experience to relax in a more private environment and process their experience with a therapist who accompanied them. One participant was audibly laughing and elected to move to a private room to avoid disturbing others. In contrast, the other reported experiencing anxiety, which he associated in part with the music in the group room. Both were administered acupuncture in a private setting.

3.3 Quantitative data collection

Recruitment yielded 17/88 individuals enrolled (19.3 %) over a 20-day window (October 6–25). Of those enrolled, 15/17 attended a scheduled session (retention 88.2 %). Among the 71 individuals who were screened but not enrolled, known reasons included IRB ineligibility (terminal illness, n = 1; age >65 years, n = 1). The remainder declined participation due to scheduling conflicts or out-of-pocket cost; reason counts were not systematically recorded. No candidates were excluded by the physician for ketamine-related medical or psychiatric contraindications at screening (0/88), no day-of-deferrals occurred, and all attendees met the pre-dose blood pressure threshold (≤150/90). Of attendees, 13/15 completed acupuncture in the group room (group-session completion 86.7 %); 2/15 elected acupuncture in a private room and are counted in overall attendance but not in the group-room completion numerator. Instrument completion was 15/15 for the initial EIS (100 %) and 6/15 at 3 months (40 %); 5/15 (33.3 %) returned the optional feedback form. All data has been summarized in Table 3.

Table 3

| Outcome | Value |

|---|---|

| Screening requests received | 88 |

| Enrolled | 17 (filled in 20 days) |

| Attended scheduled sessions | 15 |

| Retention rate | 88 % (15/17) |

| Completed acupuncture in group room* | 13/15 (87 %) |

| Initial Experienced Integration Scale (EIS) completion (24–72 h post-session) | 15/15 (100 %) |

| Initial EIS total score ( % of maximum) | Mean 74 %; range 45–100 |

| 3-month EIS completion | 6/15 (40 %) |

| 3-month EIS total score ( % of maximum) | Mean 76 % |

Table Footnotes

-

⁎Two participants completed acupuncture in a private room rather than the group room (counted in overall attendance).

3.4 Compliance and side effects

All participants completed the initial EIS within the two-week window of ketamine-augmented neuroplasticity [10]. Six participants completed the follow-up EIS 3 months after their session, without repeated reminders. There was low compliance with optional feedback (33 %) and the second round of the EIS (40 %).

No adverse side effects from the acupuncture were observed. One participant verbalized having a mild headache after the session, although it was unclear if it was related to the acupuncture, the ketamine, or some other cause. One participant with prior acupuncture experience noted heightened sensations associated with the acupuncture needles on the feedback form but did not indicate that it was a detriment to the treatment.

4 Discussion

4.1 Feasibility and future directions

Certain benefits of psychedelic experiences may be rapid and durable, while others may continue to unfold gradually or even throughout one’s lifetime as they become relevant and take on new meaning. Similarly, some effects of acupuncture are immediate (such as muscle fasciculation during myofascial trigger point release, neurological changes, and cardiovascular changes), and others (such as immune system modulation) develop more gradually [38]. As a pilot study without a control group, this research successfully demonstrates the feasibility of combining ketamine therapy and acupuncture through recruitment and retention rates of 88 %, as well as subjective tolerability. Our results indicate that these modalities may be well-tolerated in healthy volunteers seeking psychospiritual growth when combined in future research and therapeutic settings. Future controlled trials are warranted to assess efficacy for psychospiritual growth as well as for the amelioration of certain conditions. Physical monitoring during both the psychedelic experience and acupuncture could help elucidate the acute effects of these treatments when combined. Because the cohort comprised healthy volunteers with no active psychiatric diagnoses, results should not be interpreted as evidence of clinical efficacy; controlled trials in clinical populations (e.g., depression, anxiety, PTSD, chronic pain) are needed before clinical recommendations can be made.

Although two participants elected to leave the group setting, one due to transient anxiety and another because of laughter, both were still able to complete their acupuncture treatments in a private room. Transient anxiety or distress is not uncommon in the short term following a psychedelic experience, and laughter has also been reported as a typical acute response [19,39]. The ability of these participants to continue their treatments in a different setting underscores that such reactions can be accommodated without detracting from overall feasibility. This flexibility may be valuable for future studies and clinical applications, where supportive adjustments to individual needs are expected.

As part of this feasibility study, the EIS was included as a supporting measure to explore whether participants could meaningfully reflect on their integration after the combined ketamine and acupuncture session. Initial scores ranged from 45 % to 100 % with a mean of 74 %, suggesting that participants were generally able to engage with the instrument. Detailed data and item-level trends are presented in Appendix G. While not designed to test effectiveness, these preliminary results indicate that the EIS could be a useful outcome measure in future controlled studies. In that context, the scale may help clarify whether acupuncture enhances feelings of being ‘Settled,’ ‘Harmonized,’ or ‘Improved’ following psychedelic experiences. Additional instruments, such as the Watts Connectedness Scale [40], could also complement this approach, particularly in group settings where social and relational factors are central.

Psychedelic medicine, as well as acupuncture and sound meditation, can be administered in a group setting. This setting provides cost-reduction benefits for both future studies and treatment interventions. Future research may also investigate whether this setting yields intrinsic therapeutic benefits by comparing data obtained from treatments outside of a group setting.

While this pilot focused on healthy volunteers seeking psychospiritual transformation, future research may examine the suitability of combining ketamine and acupuncture for clinical conditions for which both therapies have established, yet independent, efficacy, such as depression, anxiety, post‑traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and chronic pain. For example, intranasal ketamine has shown symptom reductions in depression, anxiety (including social dysfunction), PTSD, and chronic pain in systematic reviews and meta-analyses [41–44]. At the same time, acupuncture has demonstrated effectiveness in alleviating symptoms of depression, anxiety, PTSD, and chronic pain, specifically in part by regulating stress response and promoting neuroplasticity [15,16,45,46].

To isolate the incremental effect of acupuncture, the next study should randomize participants to ketamine+acupuncture versus ketamine-only under otherwise identical conditions (set/setting, group size, music/sound, time since dosing, and therapist contact). A pragmatic randomized trial could assign individuals within sessions (or use cluster randomization by session to preserve group dynamics), with blinded outcome assessment and intention-to-treat analyses. Primary outcomes would include the EIS at 24–72 h and 3 months; secondary outcomes could include the Watts Connectedness Scale, mood/anxiety scales (e.g., PHQ-9, GAD-7), and objective autonomic indices (e.g., HRV) during/after treatment [47]. This design will allow estimation of the added value of acupuncture beyond ketamine alone while maintaining ecological validity of the group context. To support replication and standardized reporting, completed checklists are provided in Appendices H–J.

4.2 Limitations

Lack of funding for this pilot skewed the participation to people with an existing interest in this therapy not based on monetary compensation, and also prevented the use of physical monitoring such as through HRV measuring devices. While compliance with survey completion could have been increased if administered in person or by phone, surveys were purposely administered by REDCap to minimize influencing participant responses. Compensation could help incentivize compliance with outcome measures administered in future large-scale studies. Because this pilot enrolled healthy volunteers rather than a clinical population, generalizability to patients with specific diagnoses remains to be determined. Comorbidities, current medications/supplements, and alcohol use were evaluated during physician screening for safety; however, these variables were not captured in the research dataset and therefore were not analyzed or correlated with acupuncture treatment characteristics. Notably, medically supervised ketamine has not been shown to lead to subsequent misuse or transition to non-medical use [5]. While fixed prescriptions can simplify standardization, our Classical approach intentionally used day-of tailoring. We mitigated variability by specifying hard delivery limits, pulse-guided decision rules, and fidelity checks (Appendix B).

In this minimal-risk feasibility pilot, the clinical screening (HIPAA-compliant portal intake plus physician telehealth review) captured comorbidities and medications for safety purposes, but individual-level health details were not retained in the research dataset (IRB-approved) to minimize burden and re-identification risk in a small cohort. We now report the aggregate screening outcome (no exclusions) and commit to prespecifying and reporting baseline diagnoses and medication class variables in a subsequent randomized trial.

Detailed baseline comorbidities were not collected to minimize burden and re-identification risk in this small feasibility cohort; consequently, potential confounding by these factors could not be assessed and will be addressed in future controlled trials. Additionally, socioeconomic variables (education, occupation, household income, religion) were not collected in this feasibility cohort to minimize participant burden and re-identification risk in a small sample; consequently, we could not assess their potential confounding or moderating effects, and these variables will be prespecified and collected in subsequent controlled trials. Because this pilot did not include a ketamine-only control, causal attribution of effects to acupuncture is not possible; the randomized design outlined in Discussion 4.1 is planned to address this in subsequent work.

Post-experimental session, ketamine use and therapeutic interventions, including acupuncture, were not systematically tracked between the initial EIS administration and the 3-month follow-up. Some participants independently received additional acupuncture during this period, but none reported additional ketamine use. Participants who processed their experiences with healthcare providers (acupuncturists or otherwise) or within their communities may have derived additional benefits. Tracking such integration-related activities between the initial and follow-up EIS assessments could provide valuable insights in future studies. The Integration Engagement Scale [35] may serve as a useful quantitative measure to capture participant use of various integration techniques.

5 Conclusion

The results of this pilot show that there is substantial patient interest in somatic therapeutic interventions in proximity to a psychedelic experience, and that participant retention remained high through several weeks between enrollment to completion of the outcome assessment. More research is warranted to elucidate the efficacy and best practices for administering acupuncture for psychedelic experience integration. A full-scale mixed methods controlled trial could provide more information about whether acupuncture treatment yields greater benefit within the window of neuroplasticity, supporting ongoing integration following psychedelic experiences.

Data availability

De-identified, aggregate data supporting the findings of this study are included within the article and its Appendices. Individual-level raw data are not publicly available because consent did not permit the sharing of raw data.

Funding sources

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

The author declares that no generative AI or AI-assisted technologies were used in the writing process.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Marjorie Navarro: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

This research would not have been possible without the clinical support of Dr. Michael Pappas, MD and Zach Rieck, LCSW.

Supplementary materials

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.eujim.2025.102579.

References

-

[1]M.W. Johnson, P.S. Hendricks, F.S. Barrett, R.R. Griffiths, Classic psychedelics: an integrative review of epidemiology, therapeutics, mystical experience, and brain network function, Pharmacol. Ther. 197 (2019) 83–102, doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2018.11.010.

-

[2]N.K. Savalia, L.X. Shao, A.C. Kwan, A dendrite-focused framework for understanding the actions of ketamine and psychedelics, Trends Neurosci. 44 (2021) 260–275, doi:10.1016/j.tins.2020.11.008.

-

[3]J.N. Johnston, B. Kadriu, C. Kraus, I.D. Henter, C.A. Zarate, Ketamine in neuropsychiatric disorders: an update, Neuropsychopharmacol. Off. Publ. Am. Coll. Neuropsychopharmacol. 49 (2024) 23–40, doi:10.1038/s41386-023-01632-1.

-

[4]D.J. Sicignano, R. Kurschner, N. Weisman, A. Sedensky, A.V. Hernandez, C.M. White, The impact of ketamine for treatment of Post-traumatic Stress disorder: a systematic review with meta-analyses, Ann. Pharmacother. (2023) 10600280231199666, doi:10.1177/10600280231199666.

-

[5]Z. Walsh, O.M. Mollaahmetoglu, J. Rootman, S. Golsof, J. Keeler, B. Marsh, D.J. Nutt, C.J.A. Morgan, Ketamine for the treatment of mental health and substance use disorders: comprehensive systematic review, BJPsych Open 8 (2021) e19, doi:10.1192/bjo.2021.1061.

-

[6]S.J. Drozdz, A. Goel, M.W. McGarr, J. Katz, P. Ritvo, G.F. Mattina, V. Bhat, C. Diep, K.S. Ladha, Ketamine assisted psychotherapy: a systematic narrative review of the literature, J. Pain Res. 15 (2022) 1691–1706, doi:10.2147/JPR.S360733.

-

[7]J. Greń, I. Gorman, A. Ruban, F. Tylš, S. Bhatt, M. Aixalà, Call for evidence-based psychedelic integration, Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 32 (2024) 129–135, doi:10.1037/pha0000684.

-

[8]Sujas Bhardwaj, Shantala Hegde, Music and health: music and its effect on physical health and positive mental health, Sound Health Handb. Sound Music Health, 1st ed, Indus, ThinkMines Media, Chennai, India, 2022.

-

[9]M.T. Zaatar, K. Alhakim, M. Enayeh, R. Tamer, The transformative power of music: insights into neuroplasticity, health, and disease, Brain Behav. Immun. – Health 35 (2024) 100716, doi:10.1016/j.bbih.2023.100716.

-

[10]V. Phoumthipphavong, F. Barthas, S. Hassett, A.C. Kwan, Longitudinal effects of ketamine on dendritic architecture In vivo in the mouse medial frontal cortex, eNeuro 3 (2016) ENEURO.0133-15.2016, doi:10.1523/ENEURO.0133-15.2016.

-

[11]M. Wu, S. Minkowicz, V. Dumrongprechachan, P. Hamilton, Y. Kozorovitskiy, Ketamine rapidly enhances glutamate-evoked dendritic spinogenesis in medial prefrontal cortex through dopaminergic mechanisms, Biol. Psychiatry 89 (2021) 1096–1105, doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2020.12.022.

-

[12]G.J. Bathje, E. Majeski, M. Kudowor, Psychedelic integration: an analysis of the concept and its practice, Front. Psychol. 13 (2022) 824077, doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.824077.

-

[13]I. Gorman, E.M. Nielson, A. Molinar, K. Cassidy, J. Sabbagh, Psychedelic harm reduction and integration: a transtheoretical model for clinical practice, Front. Psychol. 12 (2021) 645246, doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.645246.

-

[14]V. Napadow, R.P. Dhond, J. Kim, L. LaCount, M. Vangel, R.E. Harris, N. Kettner, K. Park, Brain encoding of acupuncture sensation–coupling on-line rating with fMRI, NeuroImage 47 (2009) 1055–1065, doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.05.079.

-

[15]B. Chen, C.C. Wang, K.H. Lee, J.C. Xia, Z. Luo, Efficacy and safety of acupuncture for depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis, Res. Nurs. Health 46 (2023) 48–67, doi:10.1002/nur.22284.

-

[16]M. Li, X. Liu, X. Ye, L. Zhuang, Efficacy of acupuncture for generalized anxiety disorder: a PRISMA-compliant systematic review and meta-analysis, Medicine 101 (2022) e30076, doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000030076.

-

[17]S. Karatay, S.C. Okur, H. Uzkeser, K. Yildirim, F. Akcay, Effects of acupuncture treatment on fibromyalgia symptoms, serotonin, and substance P levels: a randomized sham and placebo-controlled clinical trial, Pain Med. Malden Mass 19 (2018) 615–628, doi:10.1093/pm/pnx263.

-

[18]C.H. Liu, M.H. Yang, G.Z. Zhang, X.X. Wang, B. Li, M. Li, M. Woelfer, M. Walter, L. Wang, Neural networks and the anti-inflammatory effect of transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation in depression, J. Neuroinflammation 17 (2020) 54, doi:10.1186/s12974-020-01732-5.

-

[19]T.M. Carbonaro, M.P. Bradstreet, F.S. Barrett, K.A. MacLean, R. Jesse, M.W. Johnson, R.R. Griffiths, Survey study of challenging experiences after ingesting psilocybin mushrooms: acute and enduring positive and negative consequences, J. Psychopharmacol. Oxf. Engl. 30 (2016) 1268–1278, doi:10.1177/0269881116662634.

-

[20]Morris, William, Transformation: treating trauma with acupuncture and herbs, Austin, TX, 2015.

-

[21]E. Chuang, N. Hashai, M. Buonora, J. Gabison, B. Kligler, M.D. McKee, “It’s better in a group anyway”: patient experiences of group and individual acupuncture, J. Altern. Complement. Med. N. Y. N 24 (2018) 336–342, doi:10.1089/acm.2017.0262.

-

[22]M. Shakur, U. Trinidad, The seed: history of the original acupuncture Detoxification Program at Lincoln Hospital, Souls 23 (2022) 36–48, doi:10.1080/10999949.2022.2104593.

-

[23]S. Hamvas, P. Hegyi, S. Kiss, S. Lohner, D. McQueen, M. Havasi, Acupuncture increases parasympathetic tone, modulating HRV – systematic review and meta-analysis, Complement. Ther. Med. 72 (2023) 102905, doi:10.1016/j.ctim.2022.102905.

-

[24]R. McCraty, New frontiers in heart rate variability and social coherence research: techniques, technologies, and implications for improving group dynamics and outcomes, front, Public Health 5 (2017) 267, doi:10.3389/fpubh.2017.00267.

-

[25]Aixala, Marc, Developing integration of visionary experiences: a future without integration. (2017). https://chacruna.net/developing-integration-visionary/(accessed March 22, 2024).

-

[26]T.L. Goldsby, M.E. Goldsby, M. McWalters, P.J. Mills, Effects of Singing Bowl sound meditation on mood, tension, and well-being: an observational study, J. Evid.Based Complement. Altern. Med. 22 (2017) 401–406, doi:10.1177/2156587216668109.

-

[27]S.C. Kim, M.J. Choi, Does the sound of a singing bowl synchronize meditational brainwaves in the listeners?, Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 20 (2023) 6180, doi:10.3390/ijerph20126180.

-

[28]H.L. Li, Hallucinogenic plants in Chinese herbals, Bot. Mus. Leafl. Harv. Univ. 25 (1977) 161–181. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41762784 (accessed January 29, 2023).

-

[29]F.P.L. Chen, Hallucinogen use in China, Sino-Platonic Pap 318 (2021). https://sino-platonic.org/complete/spp318_hallucinogens_china.pdf (accessed March 21, 2024).

-

[30]C.G. Moore, R.E. Carter, P.J. Nietert, P.W. Stewart, Recommendations for planning pilot studies in clinical and translational research, Clin. Transl. Sci. 4 (2011) 332–337, doi:10.1111/j.1752-8062.2011.00347.x.

-

[31]J. Taipale, Winnicott and the (un)integrated self, Int. J. Psychoanal. 104 (2023) 467–489, doi:10.1080/00207578.2023.2194364.

-

[32]P.E. Vlisides, T. Bel-Bahar, A. Nelson, K. Chilton, E. Smith, E. Janke, V. Tarnal, P. Picton, R.E. Harris, G.A. Mashour, Subanaesthetic ketamine and altered states of consciousness in humans, Br. J. Anaesth. 121 (2018) 249–259, doi:10.1016/j.bja.2018.03.011.

-

[33]D.B. Carr, L.C. Goudas, W.T. Denman, D. Brookoff, P.S. Staats, L. Brennen, G. Green, R. Albin, D. Hamilton, M.C. Rogers, L. Firestone, P.T. Lavin, F. Mermelstein, Safety and efficacy of intranasal ketamine for the treatment of breakthrough pain in patients with chronic pain: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study, Pain 108 (2004) 17–27, doi:10.1016/j.pain.2003.07.001.

-

[34]Neal, Introduction to Neijing classical acupuncture part 1: history and basic principles, Am. J. Chin. Med. 100 (2012) 5–14.

-

[35]T. Frymann, S. Whitney, D.B. Yaden, J. Lipson, The psychedelic integration scales: tools for measuring psychedelic integration behaviors and experiences, Front. Psychol. 13 (2022) 863247, doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.863247.

-

[36]K. Lascelles, L. Marzano, F. Brand, H. Trueman, R. McShane, K. Hawton, Ketamine treatment for individuals with treatment-resistant depression: longitudinal qualitative interview study of patient experiences, BJPsych Open 7 (2021) e9, doi:10.1192/bjo.2020.132.

-

[37]A.A. Boehmer, S. Georgopoulos, J. Nagel, T. Rostock, A. Bauer, J.R. Ehrlich, Acupuncture at the auricular branch of the vagus nerve enhances heart rate variability in humans: an exploratory study, Heart Rhythm O2 1 (2020) 215–221, doi:10.1016/j.hroo.2020.06.001.

-

[38]C. Jung, J. Kim, K. Park, Cognitive and affective interaction with somatosensory afference in acupuncture-a specific brain response to compound stimulus, Front. Hum. Neurosci. 17 (2023) 1105703, doi:10.3389/fnhum.2023.1105703.

-

[39]C. Griffiths, K. Walker, I. Reid, K.M. Da Silva, A. O’Neill-Kerr, A qualitative study of patients’ experience of ketamine treatment for depression: the ‘Ketamine and me’ project, J. Affect. Disord. Rep. 4 (2021) 100079, doi:10.1016/j.jadr.2021.100079.

-

[40]R. Watts, H. Kettner, D. Geerts, S. Gandy, L. Kartner, L. Mertens, C. Timmermann, M.M. Nour, M. Kaelen, D. Nutt, R. Carhart-Harris, L. Roseman, The Watts connectedness scale: a new scale for measuring a sense of connectedness to self, others, and world, Psychopharmacology 239 (2022) 3461–3483, doi:10.1007/s00213-022-06187-5.

-

[41]D. An, C. Wei, J. Wang, A. Wu, Intranasal ketamine for depression in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials, Front. Psychol. 12 (2021) 648691, doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.648691.

-

[42]M. Marchi, F.M. Magarini, G. Galli, F. Mordenti, A. Travascio, D. Uberti, E. De Micheli, L. Pingani, S. Ferrari, G.M. Galeazzi, The effect of ketamine on cognition, anxiety, and social functioning in adults with psychiatric disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis, Front. Neurosci. 16 (2022) 1011103, doi:10.3389/fnins.2022.1011103.

-

[43]R. Janssen-Aguilar, S. Meshkat, H.F. Al-Shamali, A. Perivolaris, J. Swainson, Y. Zhang, A. Greenshaw, L. Burback, O. Winkler, J.L. Phillips, M.W. Enns, J. Sareen, A. Nicholson, E. Vermetten, R. Jetly, R. Lanius, V. Bhat, Interventional psychiatry and emerging treatments for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD): a systematic review, Psychiatry Clin. Psychopharmacol. 35 (2025) S57–S89, doi:10.5152/pcp.2025.241027.

-

[44]C. Zaki, Beyond Anesthesia, Ketamine’s expanding role in chronic pain and psychiatric disorders, J. Integr. Neurosci. 24 (2025) 26766, doi:10.31083/JIN26766.

-

[45]C.Y. Kwon, B. Lee, S.H. Kim, Efficacy and underlying mechanism of acupuncture in the treatment of posttraumatic Stress disorder: a systematic review of Animal studies, J. Clin. Med. 10 (2021) 1575, doi:10.3390/jcm10081575.

-

[46]A.J. Vickers, E.A. Vertosick, G. Lewith, H. MacPherson, N.E. Foster, K.J. Sherman, D. Irnich, C.M. Witt, K. Linde, Acupuncture trialists’ Collaboration, Acupuncture for chronic pain: update of an individual patient data meta-analysis, J. Pain 19 (2018) 455–474, doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2017.11.005.

-

[47]F. Shaffer, J.P. Ginsberg, An overview of heart rate variability metrics and norms, Front. Public Health 5 (2017) 258, doi:10.3389/fpubh.2017.00258.