Many of the patients coming to my office are seeking acupuncture for the first time, and one of the frequently asked questions in that first appointment is how acupuncture works.

I’ll sum it up here for all interested. Since the medical research on how acupuncture works is extensive, this first post covers just the effects on connective and muscle tissue, and I will post a subsequent one on the effects on the brain and central nervous system.

Connective Tissue and the Relaxation Response

In the early 2000s, Dr. Helene M. Langevin, MD studied what happens under the skin during acupuncture.

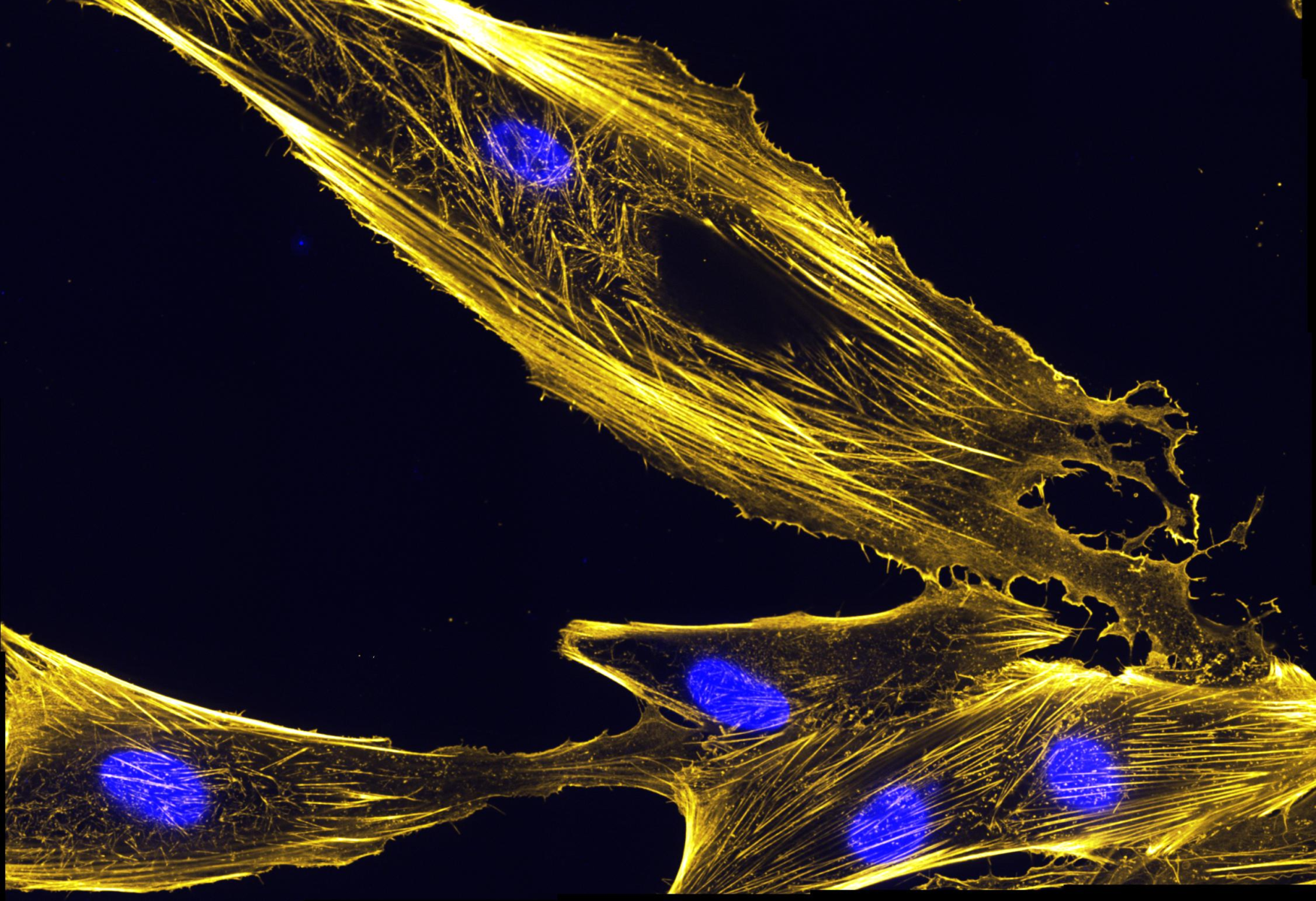

Using ultrasound, Langevin’s team found that when acupuncture needles were inserted and rotated even slightly, connective tissue wrapped around the needle, stretching it subtly [1]. Moreover, cells called fibroblasts in the connective tissue as far as several centimeters away from the needle showed reorganization of their internal cytoskeleton, becoming large and flat, for as long as the needle remained under the skin. The same reorganization can be observed by simply stretching the tissue for approximately 30 minutes, about the same length of time a patient would rest with needles in during a typical acupuncture treatment. This fibroblast-initiated cytoskeletal reorganization is required for full tissue relaxation and explains the large-scale relaxation response during acupuncture [2], in addition to its following verified pain-relieving effects in muscle tissue.

Releasing Trigger Points and Pain

What we know about acupuncture’s benefits for muscles is largely based on the work of another physician, Dr. Janet Travell, MD, in the late 30s and early 40s. Dr. Travell mapped what are called trigger points and their referred pain patterns, and would inject procaine or saline solution into the trigger points to eliminate them. Trigger points are areas of tension where the nerve ‘talks’ to the muscle cell (called a motor endplate), typically towards the middle of the muscle. This endplate becomes dysfunctional often either from bracing muscles for impact or from repetitive strain [3], creating a localized contraction that may or may not be painful [4]. Trigger points are, however, involved in nearly every pain syndrome [5]. In other words, there may not be pain where there is a trigger point, but there will most likely be trigger point(s) where there is pain.

“Dry” Needling

Over the years, experimentation with injecting trigger points with various substances, including procaine, saline solution, botox, glucose and corticosteroids, yielded similar results (regardless of what was injected) as long as the needle elicited a twitch response in the muscle. It was then hypothesized that it was the mechanical disruption of the trigger point that alleviated the symptoms, not the injection. Further studies on ‘dry needling,’ or needling without injection, showed comparable effects to injections with lidocaine [6, 7], but ‘dry needling’ was superior in its long-term reduction of pain [7]. While trigger points can be inactivated with manual techniques and joint manipulations [8, 9], dry needling appears to be a more efficient and quicker method [10]. One of my previous posts includes tips for how to get the most out of acupuncture trigger point release.

Specifically, after the local twitch response, neuropeptides involved in the development of pain (SP and CGRP) were significantly reduced in active trigger points. This corresponds with the clinical observation of an immediate decrease in pain and local tenderness after the inactivation of a trigger point [11, 12]. Not only can this reduce local, referred and widespread pain [13, 14], it restores range of motion and muscle activation patterns [15, 17, 18], and normalizes muscle efficacy [16]. In addition to the aforementioned local effects, trigger point inactivation influences remote parts of the body [14, 19, 20].

Putting it All Together

The combined effects on connective and muscle tissue are powerful and allow for increased circulation (also known as microperfusion) similar to unkinking a hose. Studies show that microperfusion increases by 75% during and even for some time after an acupuncture treatment [21], allowing for key nutrients to be brought to the area and waste removed. Altogether this explains scientifically how one can expect to obtain relief for musculoskeletal conditions through acupuncture.

Although various needling approaches without injection are commonly referred to as ‘dry needling,’ it is important that there are significant differences between schools, their specific needling techniques, and the duration of training programs. Not only do licensed acupuncturists study for years to perform these techniques, whereas other professions may offer weekend courses in ‘dry needling,’ because acupuncture needles are much finer, vastly more trigger points can be comfortably treated per session than can be with injection or even manual release. Check my blog next month for Part 2 on acupuncture’s effects on the brain and nervous system including how it stimulates certain nerves to block pain sensations along with affecting every physiological process in the body.

Works Cited:

1. Langevin HM, Konofagou EE, Badger GJ, Churchill DL, Fox JR, Ophir J, Garra BS. Tissue displacements during acupuncture using ultrasound elastography techniques. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2004;30:1173-83.

2. Langevin HM, Bouffard NA, Fox JR, Palmer BM, Wu J, Iatridis JC, Barnes WD, Badger GJ, Howe AK. Fibroblast cytoskeletal remodeling contributes to connective tissue tension. J Cell Physiol. 2011;226:1166-75.

3. Travell JG, Simons DG, Simons LS. 1999. Myofascial Pain and Dysfunction: The Trigger Point Manual. Volume 1. Johnson ES, editor. Philadelphia (PA): Lippincot Williams & Wilkins. p. 12-177.

4. Gerwin RD. 2011. Myofascial pain syndrome: unresolved issues and future directions. In: Dommerholt J, Huijbregts PA, editors. Myofascial trigger points: pathophysiology and evidence-informed diagnosis and management. Boston (MA): Jones & Bartlett. p. 263–83.

5. Dommerholt J, Bron C, Franssen JL. Myofascial trigger points; an evidence-informed review. J Manual Manipulative Ther 2006;14:203–21.

6. Cummings TM, White AR. Needling therapies in the management of myofascial trigger point pain: a systematic review. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2001;82:986–92.

7. Ga H, Choi JH, Park CH, Yoon HJ. Acupuncture needling versus lidocaine injection of trigger points in myofascial pain syndrome in elderly patients — a randomised trial. Acupunct Med 2007;25:130–6.

8. Grieve R, Clark J, Pearson E, Bullock S, Boyer C, Jarrett A. The immediate effect of soleus trigger point pressure release on restricted ankle joint dorsiflexion: a pilot randomised controlled trial. J Bodyw Mov Ther 2011;15:42–9.

9. Ruiz-Saez M, Fernandez-de-las-Penas C, Blanco CR, Martinez-Segura R, Garcia-Leon R. Changes in pressure pain sensitivity in latent myofascial trigger points in the upper trapezius muscle after a cervical spine manipulation in pain-free subjects. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2007;30:578–83.

10. Dommerholt J, Mayoral del Moral O, Gröbli C. Trigger point dry needling. J Man Manipulative Ther 2006;14:E70–87.

11. Shah J, Phillips T, Danoff JV, Gerber LH. A novel microanalytical technique for assaying soft tissue demonstrates significant quantitative biomechanical differences in 3 clinically distinct groups: normal, latent and active. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2003;84:A4.

12. Shah JP, Danoff JV, Desai MJ, Parikh S, Nakamura LY, Phillips TM, Gerber LH. Biochemicals associated with pain and inflammation are elevated in sites near to and remote from active myofascial trigger points. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2008;89:16–23.

13. Lewit K. The needle effect in the relief of myofascial pain. Pain 1979;6:83–90.

14. Srbely JZ, Dickey JP, Lee D, Lowerison M. Dry needle stimulation of myofascial trigger points evokes segmental anti-nociceptive effects. J Rehabil Med 2010;42:463–8.

15. Fernandez-Carnero J, La Touche R, Ortega-Santiago R, Galan-del-Rio F, Pesquera J, Ge HY, Fernández-de-Las-Peñas C. Short-term effects of dry needling of active myofascial trigger points in the masseter muscle in patients with temporomandibular disorders. J Orofac Pain 2010;24:106–12.

16. Ge HY, Arendt-Nielsen L. Latent myofascial trigger points. Curr Pain Headache Rep 2011;15(5):386-92.

17. Lucas KR, Polus BI, Rich PS. Latent myofascial trigger points: their effects on muscle activation and movement efficiency. J Bodyw Mov Ther 2004;8:160–6.

18. Lucas KR, Rich PA, Polus BI. Muscle activation patterns in the scapular positioning muscles during loaded scapular plane elevation: the effects of latent myofascial trigger points. Clin Biomech 2010;25:765–70.

19. Hsieh YL, Kao MJ, Kuan TS, Chen SM, Chen JT, Hong CZ. Dry needling to a key myofascial trigger point may reduce the irritability of satellite MTrPs. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2007;86:397–403.

20. Tsai CT, Hsieh LF, Kuan TS, Kao MJ, Chou LW, Hong CZ. Remote effects of dry needling on the irritability of the myofascial trigger point in the upper trapezius muscle. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2010;89:133–40.

21. Sandberg M, Lundeberg T, Lindberg LG, Gerdle B. Effects of acupuncture on skin and muscle blood flow in healthy subjects. Eur J Appl Physiol 2003;90 (1-2):114-119.